|

Abstract Pex is a preprocessor and a build management system for Pyrex, or Cython. Among other things, Pex adds the ability to conveniently write C fast numerics using numpy.ndarray, frees you from Makefiles and header files, and makes your Pyrex classes serializable, through both pickling and a faster scheme. To the user, Pex looks like a programming language that is much like Python, but with additional syntax, through which it can be made to run as fast as C in settings all the way from small numerical loops to large scale systems. Pyrex is a Python to C compiler with the added functionality of C fast function calls, an object system with C fast attribute access and method invocation, and extra syntax that allows mixing-in of C code. Cython is a close cousin to Pyrex, which adds many convenient features. Most of the functionality of the language is in Pyrex, and its author Greg Ewing deserves the majority of the credit. |

Python is a wonderful language that manages to guide you to correct expression of complex algorithms through little code. Python has a great standard library, convenient fundamental datatypes, clean and pleasant syntax, and an import mechanism with just it time compilation (to bytecode), which proves one can have complex systems without makefiles or a complicated build process. But it’s slow. On average, 50-100 times slower than C, for numerical code 100-400 times slower.

We felt that in principle there was no reason for Python to be this slow, and that by giving up very little of what makes Python great, one could make most of this speed penalty go away. Greg Ewing proved 95% of this point by writing Pyrex. However, in some ways Pyrex did not feel very pythonic, there was a lot of overhead to writing in Pyrex that was absent in Python. In order to write a complex system in Pyrex, one has to spend a lot of time on header files and Makefiles, much like with a C project. One likely also has to write a significant amount of custom code to enable objects to be serialized to disk, to print and to compare them. In our experience with complex projects, this boilerplate soaks up a large fraction of the effort, all the more painful since none of it has anything to do with the essence of the project. Pex generates all of this boilerplate for you, and then also augments Pyrex to allow you to write C fast numerics with a standard array datatype that is fully supported in Python – numpy’s ndarray (see 8).

This document is not meant to be standalone: some knowledge of Python is assumed. A great deal of functionality of Pex attempts to match Python semantics. Pex is mostly Pyrex, so if you are not familiar with it, look through Appendix B and refer to Pyrex documentation as needed. It may also be useful to skim Cython documentation, though it does not have much at the moment (recall that Cython is a fork of the Pyrex project that Pex actually uses). We will also refer to numpy, which is a substantial numerical library for python.

You should be aware that Pex is not yet a full language. This early stage of Pex was always intended as a thin preprocessor layer for Pyrex. While immediately useful, this is our first, learning, attempt at capturing a blend of Python elegance and C performance. You’ll no doubt encounter difficult to chase down compilation errors and strange limitations, many stemming from the fact that Pex does not employ a parser, but rather gets by on regular expressions. Throughout this document we will attempt to give you a flavor of these gotchas.

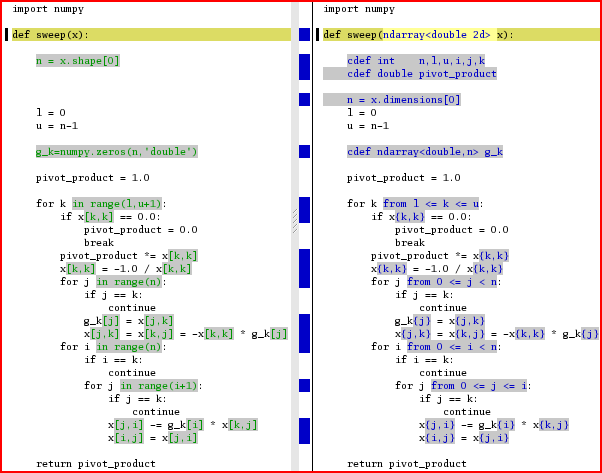

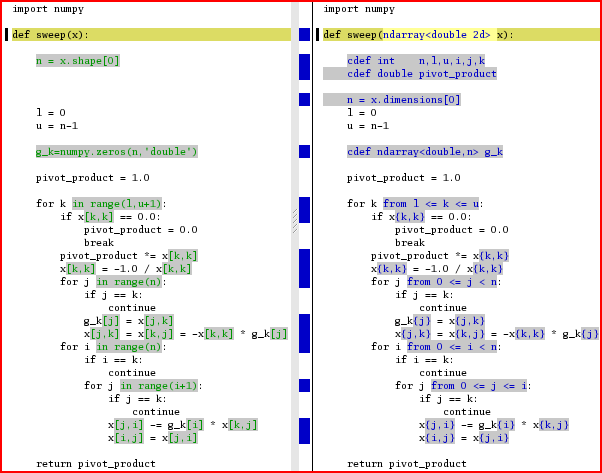

The reason to put up with Pex’s and Pyrex’s various quirks is that you can get massive performance improvements for not much difference in code. The sweep algorithm implemented in Pex is about 75 times faster than the Python implementation for a 10x10 matrix, about 400 times faster for matrices of size 100x100 and above; as you can see in the diff of the two codes, the differences are minimal. This example, while heroic, is not contrived, for numerics code you can expect to see two orders of magnitude improvement in running time.

Code snippets are given like so:

and unless otherwise specified are assumed to live in the file main.px (.px means a Pex file). Shell commands are prefixed with a “$”, thus to run the above snippet, we say:

Usually we will just show the resulting output

On occasion it is convenient to specify an entire directory tree, which we will do like so:

Here we have a main.px file in the current directory, and a directory pkg with an empty file __init__.py and a Python module file mod.py. The resulting output when main.px is ran, is:

Unless otherwise specified, if there is a main.px or main.py, it’s what is ran.

The venerable “hello world” program in Pex:

We ran it with “pex main.px” (see 2). Here is what happens behind the scenes:

Essentially, after generating the Pyrex .pyx, .pxd files from the .px file, Pex ran the following sequence of commands:

Here, in accordance with software engineering best practices, we split the functionality of hello world into two modules:

The main module, uses %pimport to bring in another module, called mod and call its function (see 7 about pimports). To see what happened behind the scenes, in excruciating detail, run pex -vall -F main.px (the -vall flag sets verbosity to all, -F forces a rebuild of everything).

Throughout the manual, we will be referring to code sections running at “C speed” or “Python speed”. Take x=x+3 for example. If x is a C int, this is effectively a C expression – it runs at C speed, but if x is a python object, this code runs at Python speed, getting translated into Python library calls along the lines of PyNumber_Add(x,PyInt_FromLong(3)). As a rough estimate, Python speed is 1-2 orders of magnitude slower than C, usually closer to 2.

We will also refer to compile time and runtime. Compile time is everything that happens to turn a .px file into a .so. Runtime is when the .so is loaded by Python, and your code is actually executing.

In Pex, you can import Python modules, and use them just as you would in Python. In particular here is an example that shows you how to access the command line:

running it from the shell we have:

The main() function has the same semantics as Python’s if __name__==’__main__’: clause. If your module has a main() function, and is executed from the command line, your main() is called. If your module is imported by something, main() is not called; for example if you have

and run pex main.px, mod’s main() is never called.

Code in the topmost scope is executed at import time, just like in Python, so in the following example, we do get output:

:-(Do not write if __name__==’__main__’: in a Pex file, Pyrex defines __name__, but it never defines it to be "__main__", thus this if statement will happily compile, but will never be true.

Imports work in Pex in the same way they do in Python, except you say %pimport instead of import. In the simplest form you say,

You may also use more complicated forms, like in Python, the full syntax is the following:

thus any of the following is valid:

To import a Pex module from Python, do:

1pkg/__init__.py

2

3pkg/submod.px

4

5 def func():

6 pass

7

8 cdef class Klass:

9 pass

10

11mod.px

12

13 cdef func():

14 pass

15

16 class Klass:

17 pass

18

19main.px

20

21 %pimport mod, pkg.submod

22

23 %pimport mod as foo, pkg.submod as bar

24

25 %from pkg.submod pimport func, Klass as baz

26

27 %from mod pimport func as gah, Klass

Imports are a weak point for Pex, Pyrex, and to some extent Python. There are some problem cases, some with errors easy to figure out, some not. Make sure you read the Gotchas section 7.2.2 below.

The pimport search path machinery in Pex, works similarly to Python. There is a PEXPATH environment variable with semantics similar to PYTHONPATH, and there is a way to alter your Pex path from inside your modules. Whereas in Python you would say

in Pex you would say

See 12 for more information on compile time configuration.

:-(Like for Python, your Pex package directories need to contain an __init__.py file in order to be importable, an empty __init__.py file is sufficient. This is really easy to forget, and really annoying to discover, so be careful.

:-(This is a trick for troubleshooting your imports. Sometimes you can have name collisions between modules, and because Python memoizes imports by module name, your import will not give you the module object you expect. Suppose at some point earlier in the program, the module foo was imported, all later import foo statements will return this module, even if you are attempting to import a different foo, and according to the semantics of the search path can expect to get it. When this happens, you’ll start seeing errors like “module object doesn’t have expected attribute”, etc. A useful way of debugging is to just print foo at the point of the error, which shows what file the module came from, and print dir(foo), which shows the module’s attributes.

A particularly nasty, and not uncommon, manifestation of this problem is when foo is a directory that happens to have an __init__.py file, which makes the directory importable. Worse yet, an __init__.pyc alone is also sufficient. To fix, remove __init__.py AND __init__.pyc.

:-(Can not do pimport *.

:-(If you wish to subclass a class that you import from another module, you must pimport that module without using from or as; do this:

not this:

:-(Can not do pimport <module>.<var>, can only do pimport <module> and then refer to the variable as <module>.<var>, or from <module> pimport <var>.

:-(Though %pimport looks like a regular statement, it is not, it causes things to happen both at compile time and at runtime. This means that the following piece of code will not do what you may expect:

The if 0: is purely runtime statement, it does not actually bind the %pimport. Here, the %pimport is still processed at compile time, but not at runtime, and bad things will happen.

In Python, [] accesses are slow. For example, make yourself a numpy array (henceforth referred to as “ndarray”), and then access it like so:

There is a lot of work that happens behind the scenes for that arr[1], here is just the partial C class stack:

All this overhead makes the [] access two orders of magnitude slower than if arr was a C double arr[] array. Pex lets you get that speed back by saying arr{1} instead, though before you are allowed to do so, you must “decorate” arr with some type information:

this arr{1} happens at C speed, as if arr was a C int * . Similarly for multiple dimensions:

Supported types for a decorated ndarray are char,short,int,double, and object.

There are a few ways ndarrays may become decorated. The simplest is when an ndarray comes in as an argument to a function:

The general syntax is ndarray<TYPE DIMENSIONALITYd>. In the above example a 2 dimensional array of shorts is passed in. The type and dimensionality are checked, and if you try to pass in the wrong thing, an NDArrayDecorationError exception will be thrown.

There are also two ways to declare decorated ndarrays, the first is non-allocating:

The intention is that at some point later, the variable will be assigned an ndarray of the right type and dimensionality. Such assignments are typechecked, and an exception will be raised if the type or dimensionality is wrong. If you access your array before allocating it with something like arr = numpy.zeros(’d’,3), you will SEGFAULT (see 18 for complete discussion of this type of error).DEATH!

The other flavor of decorated declaration is allocating:

The above is equivalent to

The syntax for one dimensional ndarray declaration is ndarray<TYPE, DIMENSION1>, for multi-dimensional: ndarray<TYPE, (DIMENSION1,...,DIMENSIONn)>.

The last way to decorate an ndarray is the following:

It is provided as a hack, to work around the fact that Pex does only shallow type analysis. For example, if an object has an attribute that is a decorated ndarray, you will not be able to get the fast {} accesses outside of that object:

You must do the same to access a decorated ndarray attribute of a base class:

Note that you can only use %decorate with a typed, cdef’d ndarray (see B.2.4 for discussion about typed vs untyped objects).

Creating ndarrays using the numpy API is slow, the creation calls, like numpy.zeros(), have to plumb through the Python runtime. Pex provides a faster alternative:

where type is one of the decoration types char,short,int,double, or object. Here is an example:

The allocating declarations, e.g. cdef ndarray<double,(17,10,5)> arr, call these functions. For something even faster, there are also these calls

They have the same API as ndarray_zeros calls, but do not zero out the contents of the allocated ndarray, returning the memory as is. Thus the allocating declaration:

is equivalent to

and is slower than

For arrays of dimensionality bigger than 4, you are left with calling the Python numpy API.

Slicing ndarrays – arr[4:7] – is slow. Things have to plumb through the Python runtime to get to the fast numpy code that creates the slice (note that an ndarray slice is not a copy, but a “view” into the parent array). Pex provides fast, “decorated” slices – arr{4:7}. The general idea is that for each dimension you specify a start:stop. Either start or stop can be negative, if so it is counted off the end. Either can be missing, if start is missing it is assumed to be zero, if stop is missing it is assumed to n, where n is length of the dimension. Either can go off the ends of the array, and is clipped to be inside [0,n]. These semantics come from Python, see python documentation for a more complete discussion. Python slices can also have a 3rd argument – stride – but this is not supported for decorated slices. Here are some examples:

similarly for multiple dimensions:

1def main():

2 cdef ndarray<object,(2,4)> arr

3 cdef int i

4

5 for i from 0<=i<4: arr[0,i] = ’a’ + str(i)

6 for i from 0<=i<4: arr[1,i] = ’b’ + str(i)

7

8 print "␣␣arr\n",arr

9 print "\n␣␣{0:1,2:4}\n",arr{0:1,2:4}

10 print "\n␣␣{:1,2:}\n",arr{:1,2:}

11 print "\n␣␣{:,:}\n",arr{:,:}

12 print "\n␣␣{1,0:1}\n",arr{1,0:1}

13 print "\n␣␣{0,-2:}\n",arr{0,-2:}

14 print "\n␣␣{:,2}\n",arr{:,2}

One of the supported types for decorated ndarrays is object, it is different from the other types char,short,int,double. The others are primitive C types, whereas each object is a Python object, and thus has an associated reference count, which is how garbage collection works in Python. Pex does the right thing for the reference count as objects are read and written to the array.

When you assign to a decorated ndarray, or when you create one by decorating an argument to a function, the operation is type checked at runtime to make sure an ndarray of the right type and dimensionality is coming in. In the following example we attempt to assign an ndarray of an incorrect type:

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_ndarray_type_check† | On/off flag for typechecking of decorated ndarrays | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_ndarray_type_check = [True | False]

| ||

:-(If you wish to turn off typechecking of function arguments, be sure to put the pragma before the function prototype:

Were you to put the pragma in the function body, checks turn off for assignments inside the body, but not for function arguments.

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_ndarray_bounds_checks† | On/off flag for bounds checking of {} accesses to decorated ndarrays | False |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_ndarray_bounds_checks = [True | False]

| ||

Normal {} accesses to decorated ndarrays are not bounds checked - hence their speed. They are just like C array accesses, you may read off the end of the array and thus get garbage, or write off the end of the array and thus corrupt memory. Pex allows you to turn on bounds checking, all the {} then become slow (a 50x50 matrix multiply runs 20 times slower with bounds checks on), but safe, the array bounds are checked for every access. Turning on bounds checking is probably the first thing to try if your program coredumps.

Here we access off the end of the array, and without bounds checking, get no errors:

and here is the same code with bounds checking turned on:

There are two ways to turn on bounds checking: using the pragma, as shown above, or passing -b to the Pex command line.

:-(If you wish to turn on bounds checking, all assignments to elements of decorated ndarrays must appear as the first thing on a line, do this:

instead of this:

:-(SLOWTo get the lengths of an ndarray, use .dimensions instead of .shape, do this:

not this:

Though they look similar, .shape is a Python tuple, getting it as an attribute of an ndarray is slow, and accessing its elements is slow. When you use .dimensions things run a C speed, since dimensions is a C attribute of the ndarray and is a C array. Be careful, as it is a C array, its accesses are not bounds checked.

:-(DEATH!Do not use negative indices with {} accesses. If you do, you’ll access garbage memory from before the beginning of the ndarray, same as would happen with a C array. Turning on bounds checks (see 8.2.6) will detect this error.

:-(Can not have global decorated ndarrays.

:-(Can not do

must do

:-(If you have a decorated ndarray as an attribute of a cdef class, you can not access it with {} outside of the class, or even in subclasses. This is a result of Pex’s lack of an honest type system. See 8.2.1 for how to overcome this limitation with %decorate.

:-(Can not use {} accesses inside declarations, e.g. can not do cdef int x=arr{i}.

:-(Believe it or not, {} are erroneously treated as accesses even inside strings, so the following:

will error unless you happen to have a 2d decorated ndarray named arr in the scope.

:-(SLOWYou must make sure index variables you use with {} accesses are cdef’d ints, otherwise things will be slow:

In the snippet above, i is a Python object, and gets converted to a C int for every {} access, and thus every time through the loop. Instead do:

:-(SLOWUse the following loop form:

instead of

Otherwise things will be slow (this is Pyrex syntax that allows you to write C fast loops).

This can happen in several ways. For one, due to its limitations, Pex is only able to track simple, arr= <...> style assignments, and for example does not see arr, b = <...>. Thus the following example silently corrupts memory:

As a hack around this, assign the array to itself, this forces unpacking of the internals:

Here is another way memory can get corrupted, suppose you have a decorated ndarray that is a class attribute. From inside the class method, you call another class method which re-assigns the attribute:

The above corrupts memory, you need to add me.arr = me.arr after me.change() in func to force the internals to be re-unpacked after the call to change.

:-(Pex gives you two ways to declare class attributes (see C.1 for full discussion), in the class preamble, and inside the __init__ method. Allocating ndarrays declarations, however, may only be declared inside the __init__ method, therefore do this:

not this:

Non-allocating declarations you may still put in the preamble:

When you write a cdef class in Pyrex (see B.2.3 about why you may want to), a lot of the niceties you get for free with Python classes go away. Some of the downsides: you can’t print the resulting objects, can’t compare them for equality, can’t access their attributes from Python, and most importantly can’t automatically write/read them from disk (“pickling” in pythonese). Pex brings a lot of these niceties back, provided your cdef class is “modest” – its attributes come from a restricted set of types.

To make yourself a modest cdef class, restrict your attributes to the following types:

Thus the following is a modest cdef class:

and the following is immodest:

If you further restrict yourself to only the primitive C types and decorated ndarrays of any simple numerical type, e.g. anything but object (see 8 about decoration), you get an “unspoiled” class, which gets all the niceties of a modest class, and also fastio (see 9.2.7) – a serialization method that is about 10-12 times faster than pickling. Here is an unspoiled class:

and here is one that, while modest, is not unspoiled:

This class is spoiled because the ndarray me.arr is not decorated.

Each of the niceties described below, has its own pragma switch, but there is also one pragma that turns off all of the automatically generated methods described in this section:

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_gen_all_off† | On/off flag to control the generation of all convenience methods for modest and unspoiled classes | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_gen_all_off = [True | False]

| ||

cdef class requirements: modesty

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_gen_strmeth† | On/off flag to control the generation of the __str__() method | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_gen_strmeth = [True | False]

| ||

The __str__() method is called by Python when you attempt to print an object, or convert it to a string. If it is absent, a less exciting string is produced, showing the object’s type and memory address. For example, this is what you get when you turn off __str__() method generation:

One possible reason to turn it off, is if you intend to write a custom __str__() method.

cdef class requirements: modesty

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_gen_equalmeth† | On/off flag to control the generation of the _equal_() method | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_gen_equalmeth = [True | False]

| ||

This method allows you to compare two modest cdef classes:

Gotchas

:-(SLOWUnless all of your attributes are primitive C types, the _equal_() will happen at Python speeds. In principle, for attributes that are cdef classes or ndarrays it could be C fast, but at the moment isn’t.

:-(This is a cdef method, and so not callable from Python directly. However you can access it through == and !=, see next section.

cdef class requirements: modesty

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_gen_richcmpmeth† | On/off flag for the generation of the __richcmp__() method | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_gen_richcmpmeth = [True | False]

| ||

When Pyrex sees a == or != comparison between two cdef classes, it calls the __richcmp__() method of one of the objects. If this method is absent, the two objects are compared based on their memory address, thus even if two instances have every attribute the same, they will never be equal:

Pex generates this method to call the generated _equal_() method (see previous section), and this causes the == and != checks to happen based on the actual contents of the two objects, not just their memory addresses:

Gotchas

:-(SLOWThese == and != checks are slow because they plumb through Python.

cdef class requirements: modesty

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_gen_dictcoercion† | On/off flag for the generation of the _todict_() and _fromdict_() dictionary coercion methods | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_gen_dictcoercion = [True | False]

| ||

Attributes of cdef classes are not visible from Python. This is illustrated by the following example where we are not able to access the attribute i from main.py:

To overcome this limitation, Pex generates two methods for your cdef classes: _todict_() returns the cdef class’ attributes in a dictionary, _fromdict_() sets them from a dictionary:

Gotchas

:-(Any extra keys in the dictionary that is passed into _fromdict_() are ignored. For example ob._fromdict_({’i’: 17, ’rubberchicken’: True}) would have worked just as well in the above example.

cdef class requirements: modesty

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_gen_pickle† | On/off flag for the generation of the __reduce__() and __setstate__() pickling methods | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_gen_pickle = [True | False]

| ||

Normal Pyrex cdef classes are not “picklable” (pickling is Python’s term for serialization – writing and reading objects from disk). Pex automatically generates two special Python methods __reduce__() and __setstate__(), which make your cdef classes picklable. It is unlikely you’ll ever need to call these functions directly.

A thing of note is that the Python’s object copy machinery also works through these methods, and so their presence makes your cdef classes copiable:

See the next section for a faster serialization method.

Gotchas

:-(If you have a list of cdef class objects you wish to pickle, do not dump them one at a time like so:

Instead do the whole list at once:

Pex dumps a type signature once for every dump invocation, thus once for every object when you write them one at a time. This unnecessarily, and possibly substantially, increases your storage requirements. In the second case, when you write the entire list at once, the type signature is written only once.

cdef class requirements: must be unspoiled

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_gen_fastio† | On/off flag for the generation of the _fastdump_() and _fastload_() fastio methods | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_gen_fastio = [True | False]

| ||

If your cdef class is unspoiled, in addition to being modest (see 9.1), Pex will generate the two methods, _fastload_() and _fastdump_(), which implement a serialization scheme called “fastio”. It is slightly less convenient to use than pickling, but is 10-12 times faster. Here is an example showing basic usage:

One common use case is to read in several cdef class objects using fastio. In order to call the _fastload_() method, you must have an instance of the cdef class, but it makes no sense to create one if its contents are immediately overwritten by the _fastload_() call. For this reason Pex provides the pex_create_uninitialized() function (see 10), which instantiates a cdef class without calling its constructor – all attributes that are primitive C types are set to zero, all attributes that are Python objects are set to None. The following example illustrates this case:

You can also use fastio to send cdef classes over a socket:

1import pickle

2

3cdef class item:

4 cdef int i

5

6# WRITE

7

8list = [item() for i in range(100)]

9

10cdef item x

11

12file = open(’tempfile’,’w’)

13pickle.dump(len(list),file)

14for x in list: x._fastdump_(file)

15file.close()

16

17# READ

18

19list = []

20

21cdef item y

22

23file = open(’tempfile’)

24n = pickle.load(file)

25for i in range(n):

26 y = pex_create_uninitialized(item)

27 y._fastload_(file)

28 list.append(y)

29file.close()

Gotchas

1datatype.px

2 cdef class item:

3 cdef int i

4 cdef double d

5

6client.px

7 % from datatype pimport item

8

9 import socket

10

11 HOST = ’localhost’

12 PORT = 33838

13

14 if 1: # setup connection

15 s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

16 s.connect((HOST,PORT))

17

18 name = str(s)

19 sfile = PyFile_FromFile(c_fdopen(s.fileno(),’w’),

20 name, ’w’, c_fclose)

21

22 cdef item x = item()

23

24 x._fastdump_(sfile)

25

26server.px

27 % from datatype pimport item

28

29 import socket

30

31 HOST = ’localhost’

32 PORT = 33838

33

34 if 1: # setup connection

35 s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

36 s.bind((’’, PORT))

37 s.listen(1)

38 s_conn, addr = s.accept()

39

40 name = str(s_conn)

41 sfile = PyFile_FromFile(c_fdopen(s_conn.fileno(),’r’),

42 name, ’r’, c_fclose)

43

44 cdef item x = pex_create_uninitialized(item)

45

46 x._fastload_(sfile)

47

48 print ’received’,x

:-(These are cdef methods, and as such, are not visible from Python.

:-(If you have an attribute that is a decorated ndarray that has become non-contiguous in memory, the _fastdump_() will fail. An ndarray may become non-contiguous if it is a slice from another ndarray with a slice step bigger than 1. You may perhaps restore its contiguousness with:

but you are really off the reservation with this one. Note that if this works, it will be a full copy of the array, and also you may only do this from Pex, not sure how to do it from Python.

The above coredumps because y, while declared, was never instantiated (see 18 for complete discussion of this kind of an error). Before calling y._fastload_() you must first instantiate y like this y=item() or this y=pex_create_uninitialized(item).

cdef class requirements: none

| pragma | purpose | default |

| pragma_gen_hashmeth† | On/off flag for the generation of the _hash_() method | True |

† set with %whencompiling: scope.pragma_gen_hashmeth = [True | False]

| ||

This function returns the memory address of the object. This function is needed because if an object has a __richcmp__() method, but not a __hash__() method, Python will not allow the object to serve as a key to a hash:

:-(This is not a real hash, it’s just the memory address of the object.

cdef class requirements: none

You’ll probably never need to call this function directly, it is used by the pickling and fastio machinery. Here it is in any case, it gives the C type signatures of all the attributes:

Some of the methods described above depend on each other, for example __str__() on _todict_(). If you run Pex with the -W command line flag, you will get warnings if you’ve turned off some method, but not the methods that depend on it:

If you wish to write your own implementation for any of the methods above, turn the method(s) off with a pragma. For pickling or fastio, you’ll probably want to look at Pex generated code first, to get an idea of what the method is supposed to do.

Sometimes, as in the case of fastio (see 9.2.7), you may wish to quickly instantiate your cdef class foo:, without going through the constructor. You may do so using pex_create_uninitialized(foo), like so:

All attributes that are primitive C types are set to zero, all attributes that are Python objects are set to None.

Gotchas

:-(Though technically pex_create_uninitialized() may take any type object as its one argument, do not call it with anything other than a Pyrex cdef class, e.g. don’t do this:

Bad things may happen.

Pex supports the following primitive C types:

| bool | 1 byte | + |

| char, uchar | 1 byte | + |

| short, ushort | 2 bytes | ++ |

| int, uint | 4 bytes | ++++ |

| int64, uint64 | 8 bytes | ++++++++ |

| float | 4 bytes | ++++ |

| double | 8 bytes | ++++++++ |

Here is an example where we print the size of the type and the maximum value:

1 # MAX VALUE

2cdef bool b = cTrue

3cdef char c = 0x7f

4cdef uchar uc = 0xff

5cdef short s = 0x7fff

6cdef ushort us = 0xffff

7cdef int i = 0x7fffffff

8cdef uint ui = 0xffffffff

9cdef int64 i64 = 0x7fffffffffffffffL

10cdef uint64 ui64 = 0xffffffffffffffffUL

11cdef float f = 3.40282346638528860e+38

12cdef double d = 1.79769313486231570e+308

13

14print ’bool’, sizeof(bool), b

15print ’char’, sizeof(char), c

16print ’uchar’, sizeof(uchar), uc

17print ’short’, sizeof(short), s

18print ’ushort’, sizeof(ushort), us

19print ’int’, sizeof(int), i

20print ’uint’, sizeof(uint), ui

21print ’int64’, sizeof(int64), i64

22print ’uint64’, sizeof(uint64), ui64

23print ’float’, sizeof(float), f

24print ’double’, sizeof(double), d

All variables of these types are pure C variables, all arithmetic and boolean expressions with them are compiled directly to C, and so run at C speed, but see 17 for situations when such variables are upcast to Python and so become slow.

In the example above, we added the suffix “L” to the constant we assigned to i64. Were we to do this:

the C compiler would complain with something like:

The C compiler does not like integer constants (also known as “literals”) that are bigger than what can fit into 4 bytes. To appease it, we append the “L”:

An unsigned int can be bigger than a signed int, so when assigning something big to a uint64, append a “UL”:

Now, lets say you are ready to get serious, and want to push some big numbers around, numbers even bigger than 8 bytes. Python supports arbitrary precision integers, to specify such a literal, add the suffix “pyL” to your number:

which will get translated to the C code:

All operations on such numbers will be much slower than operations on primitive C types.

Gotchas

:-(Do not confuse these types with the ones available for ndarray decoration (see 8 for those).

you get a strange compiler error. This happens because behind the scenes your code is translated to the following C code (roughly):

Of course c can never be less than zero, being unsigned and all, hence the compiler warning. This is a Pyrex limitation, heed your compiler warning and code around this somehow, for example assign first to an int and if that succeeds assign to your unsigned variable. Same problem exists for ushort, but due to Pyrex’s internal architecture, not for uint or uint64.

Using the %whencompiling directive, you can change the flags passed to the C compiler or linker, set pragmas, and in general execute arbitrary Python code at the time your .px file is compiled into a .so file. For example:

ran with

causes Pex to execute your print statement while compiling this main.px into a main.so. If you run Pex again, the print will not be executed:

because main.so was already compiled.

Pex gives you access to two objects in your %whencompiling code, env and scope; here is what they contain:

These two objects contain the entirety of Pex’s internal state during compilation, though the only attributes you’ll probably ever touch are: env.path, env.cc, env.link, and scope.pragma_*.

For example, to add a -Wall flag for the C compiler, do:

See the next section for how to use this C compilation configuration machinery to link with external C code.

Another useful case: suppose you wish to have some set of your Pex modules have a common, extra directory in their import search path. You can make a Python module that fixes up your path to be what you wish, and then have all your Pex modules import and use it in their %whencompiling directives:

One thing to note which can otherwise be a source of confusion, is that env.path has special semantics. The paths you add are added to both the compile time search path that Pex uses to look for modules, and also to Python’s sys.path at runtime.

1pathfix.py

2 def fix(pex_env):

3 if ’../some/funky/path’ not in pex_env.path:

4 pex_env.path.append(’../some/funky/path’)

5

6main.px

7 %pimport mod_I

8 %pimport mod_II

9

10mod_I.px

11 %whencompiling:

12 import pathfix

13 pathfix.fix(env)

14

15mod_II.px

16 %whencompiling:

17 import pathfix

18 pathfix.fix(env)

The scope object contains, among other things, the various pragmas (see D for full listing) that you can use to control what happens during compilation. The scope object has slightly different semantics than env, any changes you make to it have effect in your current scope (e.g. current indentation level), and any child scope, but not outside. For example:

setting scope.pragma_gen_strmeth=False in the topmost scope, turns off generation of the __str__ method (see 9.2.2) for the entire module – neither class I or II will have it, whereas the following:

turns it off for class I, but not class II.

Here is an example showing how to use the functionality described in the previous section to setup your compilation to link with external C code.

1main.sh

2 #!/bin/sh

3 set -x # echo shell commands

4 (cd C_src && gcc -c C_module.c -o C_module.o) # compile our C module

5 $PEX prog.px # run the pex module

6

7C_src/C_module.c

8 #include <stdlib.h>

9 #include ”include/C_module.h”

10

11 vec *vec_create(unsigned object_size, unsigned length) {

12 return malloc(object_size * length);

13 }

14

15

16C_src/include/C_module.h

17 typedef void vec;

18 vec *vec_create(unsigned object_size, unsigned length);

19

20

21prog.px

22 %whencompiling:

23 env.cc.append(’-I./C_src/include’)

24 env.link.append(’C_src/C_module.o’)

25

26 cdef extern from "C_module.h":

27 ctypedef void vec

28 vec *vec_create(unsigned object_size, unsigned length)

29

30 cdef vec *v

31 v=vec_create(4,100)

32 print ’0x%x’%<int>v

33 print

Refer to Pyrex documentation for more complete information about interfacing with C code:

Pex attempts to make the vigorous experience of a C coredump a tad more civilized. You, gentle reader, will of course never encounter such a bug in your own code, but in case you ever have to run someone else’s, Pex registers a signal handler for SIGSEGV, SIGFPE, SIGBUS, and SIGABRT that attempts to recover the C stack and print the backtrace:

Gotchas

:-(At the time this signal handler is called, memory is corrupted, and so anything may happen. For example, as has been observed a few times, “attempting backtrace..” may get printed, and then the program will hang. If you prefer the normal core dump behavior, turn this functionality off by adding -nobt to the Pex command line.

:-(This functionality is on by default, you may turn it off by using -nobt flag on the command line (see 15 about command line usage), but if you import any Pex modules not so compiled, the signal handler will get registered again.

To see what Pex is doing, in exhausting detail, run it with full verbosity:

If Pex is not run directly, but is involved in a pex.pimport() call from python, you can still turn on verbosity by setting an environment variable:

Pyrex handles exceptions by checking a global error variable after every call to a def or a cdef function. In case this is a performance problem, or a function can not possibly throw an exception, Pex allows you to turn this check off by adding except exits to the function prototype:

The except exits clause also makes sense for functions that can not possibly throw a python exception, like those in external C libraries (see E for examples of this use in builtin.pxi). See Pyrex documentation about error return values for a more complete discussion of the except clause in function prototypes.

Gotchas

:-(If the return type of a function is a python object, except exits has no effect. In the following example, the return type is omitted and thus defaults to a python object. As a result, the exception is plumbed through:

SLOWcdef bool x = True is slow, use cdef bool x = cTrue. Also note that x is True is slow, as x gets upcast to python.

SLOWBe careful with loops, for i from 0<=i<n is slow if i is not a cdef’d int.

SLOWIf you have an expression that is all cdef’d variables, it will run at C speed; however if you happen to have a single variable in the expression that is a python object, things will automatically and silently be upcast to Python and will become slow. It is easy for this to happen, and hard to detect, since by just looking at the expression you can not tell what its constituent variables are – cdef variables or python objects. See B.2.2 for more information on this topic. Your best bet, if things are not running as fast as you expected, is to look at the generated C code, and see what is actually happening.

SLOWUse except exits when declaring prototypes for external C functions, see 16 for full discussion.

SLOWBe careful with object attribute access, x.a will run two orders of magnitude slower, if x is a python object, rather than a cdef class. See B.2.3 for more information.

SLOWMake sure to give a cdef function a return type. If you don’t specify one, it defaults to a python object, and will return the Python None, even if you don’t have any returns.

What happened, is that x was accessed before it was instantiated, we should have done an x=item() first. Since we did not, the value of x was None, which we then proceeded to access as if it had type item. None was cast to type item, and then the memory address of where attribute a would have been was accessed. This got us a random memory location; had we written to the attribute, we would have corrupted the None object, and had we called a cdef’d method of item, we would have called a random memory location. BE SURE TO INSTANTIATE ALL YOUR CDEF OBJECTS, INCLUDING NDARRAYS, BEFORE ACCESSING THEM.

:-(The semantics of the Python __path__ are not supported.

:-(The pex directory must be installed in your Python path in order for the compiled Pex modules to be importable and usable.

:-(Pex does not handle Mac ‘\r’ terminated files.

:-(The mod operator % gives different results for negative numbers depending on whether the variable you apply it to is a C variable or a Python variable. Therefore if your negative number is in a C int you’ll get one answer, if it is in a Python int you’ll get another:

This can be especially confusing, because at times it’s hard to keep track of whether the result of an expression is a C value, or a Python value (see B.2.2 for a description of how and when Pyrex converts between C and Python variables).

:-(In some situations, Pyrex does not complain if you define the same variable with two different types, the following does not cause a compile or runtime error:

In the above, the last declaration wins.

:-(Pyrex does not directly warn if the name of a class attribute clashes with a member function, but instead gives you mysterious errors:

:-(Static variables are not supported, use global variables instead. Global variables have the same semantics as C globals.

:-(Do this:

not this:

or you’ll get a mysterious PexUnexpectedInternalError.

:-(If you turn off generation of all special class functions (see 9), and have nothing in the class except variable declarations, the variable declarations will get sent to the header file, the class body will become empty, and you’ll get a confusing syntax error. Do this:

instead of this:

:-(To assign a character literal, you must use the following hack:

Though contorted, the code still runs at C speed.

:-(Be careful with multi-line statements, they can be fragile due to Pex’s lack of parsing. For example, the following causes a syntax error:

because behind the scenes the line gets converted into def func(a,# informative comment b):.

:-(Be careful with ‘:’ and ‘;’, don’t try to combine too many things into one line, for example the following is a syntax error:

:-(Be careful with ‘:’, ‘{’, and ‘}’. Their liberal use, while legal Python and Pyrex syntax, may easily screw up Pex’s regular expression based processing, for example the following wouldn’t be recognized as a function prototype:

:-(If you compile your Pex modules optimized, you want to also pass the -fno-strict-aliasing to the compiler – this is the default. It slows things down slightly, but without it, with a non-trivial probability, Pyrex’s object system breaks (see 12 about how to configure the compilation).

:-(If you get a “⟨some_type⟩ is not the right type of object” error, clean and rebuild everything, this may mean that for some reason Pex’s rebuild mechanism has failed.

:-(Triple quoted strings are supported, but with a large caveat – a lot of unnecessary processing continues inside the string, and thus Pex will insist that parenthesis be balanced, that string quotes be balanced, and that if you have a “a{3}”, there must be a decorated ndarray “a” in scope, of the right dimensionality. On the positive side, if you use triple quoted strings, you’ll be forced to use more better English, as you’ll be unable to use contractions like “can’t”, which cause an error due to introducing an unmatched “’”.

:-(This is a big one, if you have a module with a cdef class, and this module also has a function that takes this cdef class as a typed argument, you can not import this module through a package – you can do import mod, but not import pkg.mod. The following breaks:

:-(In the following declaration:

the attribute i is NOT static, it is a regular class attribute. It is easy to confuse it for a static, because in Python, static variables are declared as follows:

:-(If you have a cdef attribute in a derived class, with the same name as a cdef attribute in the base class, the base class attribute is not replaced, both still exist:

1cdef class base:

2 def __init__(me):

3 cdef int me.x=3

4

5 def func(me):

6 print ’base.x’,me.x

7

8 def set_base(me, int x):

9 me.x=x

10

11cdef class derived(base):

12 cdef int x

13

14 def func(me):

15 base.func(me)

16 print ’derived.x’,me.x

17

18cdef derived d = derived()

19

20d.func()

21d.x = 7

22print

23d.func()

Pex is primarily targeted for Unix, though everything works on MacOS, except for backtraces on SEGFAULT. Pex is probably not too far from working on Windows with gcc, but does not at the moment.

We’d like to thank Greg Ewing for creating Pyrex, and making Pex possible. Through our usage of Pyrex, we’ve grown continually more impressed and are now left with a firm conviction that it is a technical tour de force. We’d like to thank the folks at the Cython project for augmenting Pyrex with many convenient and useful features. Finally, we’d like to thank our colleagues at PNYLAB for gallantly blowing themselves up on a wide variety of exciting mines as Pex was being developed, and who continue to deal stoically with some of Pex’s more rude quirks.

This version of Pex is our first attempt at creating a language that achieves performance of C, but retains most of the elegance and clarity of Python. As a first attempt it is rough around the edges, but we believe it is immediately useful, and are shifting our entire codebase into Pex. Pex gives the ability to write C fast numerical loops without any special contortions, and C fast large scale projects through the virtue of having objects with C fast attribute and method access. Through Pex’s mirroring of the Python import mechanism, large projects do not need to have any build infrastructure, and much of the boiler plate code generally required for large projects (e.g. to quickly serialize objects to disk or over sockets), is automatically generated. This, largely performance oriented functionality, lives alongside the ability to mix in Python code and classes, and thus get the full niceties of the Python language. In fact, things mix together so seamlessly, that it can be a problem at times to figure out whether you are writing C fast code or not.

It is our belief, reinforced throughout our time working on Pex, that this is something missing in the world, and not for any good technical reasons. It is eminently possible to have a language that gets down to the iron, runs at C speeds, and has no surprises in generated assembly, but at the same time guides you along to a clear, succinct and correct expression of complicated systems and algorithms. We think Pex is a good first step towards addressing this lack.

The current version of Pex does not allow for naked cdef functions to be directly visible in the Python environment. This limitation is a historical accident: Pex was initially layered over an early version of Pyrex that did not have this feature. Indeed, exporting naked functions from one Pex module to another is only partially supported.

For all our examples, we consider how to wrap the Pex/C routine sqrt.

The standard method to make cdef functions visible to the Python environment is by defining a Python interface to the function within the Pex file. For example, one may write:

One can then import py_sqrt into the Python world; calls to py_sqrt are thus forwarded to sqrt. The reason this works is that when a Pex file is compiled, its Python functions have access to all of the cdef functions within this file. Then, when the compiled module is imported into a Python environment, the Python functions (and methods) are made visible to the Python environment.

This indirection has a price: one has to go through a thin layer of Python code to access the cdef function. This “thin” layer may very well take longer than the actual invocation of the cdef function itself. However, this cost is often immaterial: if one is wallowing in Python, the cost of a single extra Python call is comparatively small.

However, there are circumstances in which one may sensibly wish to avoid any Python overhead. For example, given a function f, one may wish to compute f(x) for each value x in some ndarray v, and store the result in another ndarray, out. Such a basic mapping operation is a clear candidate for implementing in Pex. One would like to make a mapper, pass it a function, and have it construct an object that maps vectors to vectors, without going through any Python layers (aside from the initial call).

To avoid the Python layer, we can wrap cdef functions as instances of class objects. Thus, we can wrap sqrt as follows:

We can then import py_sqrt and use it as we would any Python function (note that f(x) is syntactic sugar for f.__call__(x)).

The problem with this simple approach is that we cannot easily pass py_sqrt to some other general Pex routine, since each wrapped function has a distinct type. However, this problem is remedied using subclassing.

Since Pex has a rigid type system, we have to be a little bit cleverer in order to obtain general routines. We mentioned that it would be nice to wrap a routine so that it would operate on vectors at a time (a map operation). Due to typing issues, we cannot hope to make a truly general mapping object. But we can be reasonably general. Suppose we want to take a function f that maps a double to a double, and create a new (mapping) function fv that maps an ndarray of doubles to an ndarray of doubles. We first define a dummy class, function_dd, that captures the idea of mapping a double to a double:

Then, we can wrap the sqrt function with its own class, but specify that this is a subclass of function_dd:

We can use py_sqrt as before, and it will compute the specific function we want. However, since it is a subclass of function_dd, other routines can treat it as a generic function from doubles to doubles. Thus, we can write:

After importing py_sqrt and mapper, we can set vsqrt=mapper(py_sqrt), giving a routine that computes the square root of each element of an ndarray (of doubles).

It should be noted that we still have an intermediate layer - the wrapped function must call its apply method which then calls the actual function. However, this layer is much, much faster than going through python.

It seems wasteful to make an entire class object for each function we would like to wrap. We can be more economical by making a single type, and performing invocations of this type within the pex file.

Most of this example is straightforward. We create a specific instance of the wrapper object, and set it to a specific function. But why are we using two variables, px_sqrt and py_sqrt? We need to explicitly declare a variable to be of type wrapper so we can access the set method. Then we need to make it visible to the python world, so we have a second variable, py_sqrt that is a python object (this is the default type when a variable has not been explicitly typed).

Now, we should be able to have a single expression that generates the wrapper object as a subexpression, then assigns it without ever being assigned through an extra variable. However, in our attempts, strange things happened: The compiler perversely tried to convert an object of type raw_dd to a python object, which it cannot do. Using explicitly typed intermediate variables seems to guide the compiler past this pathology.

With such ready access to the raw functions, we can rewrite the mapper object to be much more efficient, achieving something much closer to full speed.

:-(While this method is certainly more efficient, the resulting objects will not be pickleable. Indeed, to compile this code, we needed to set the following pragmas at the beginning of the file:

Thus, any object that is built up of such objects will be unpicklable. Use this method at your peril!

The mapper function we have created is very particular in the type of the function it accepts. But suppose we have a Python object that maps doubles to doubles. Why can’t we use the mapper object on it? Let us ignore the obscenity of performing ones trivial bookkeeping at C speed while computing the actual function at Python speed. We might argue that we shouldn’t have to to the trouble of reimplementing mapper in Python, or that we are quickly prototyping in Python a function that we later intend to implement in Pex.

The problem is that the mapper object wants an object of a particular type (function_dd), and even if the Python object behaves like a function_dd object should, it just doesn’t smell right. However, we can make a simple wrapper that converts an arbitrary object to a function_dd object:

Note that whenever me.obj(x) is evaluated, a run-time type check of the answer is performed to make sure that it is a double.

This section is not intended to be a standalone description of Pyrex, for that please refer to the official Pyrex documentation. Also keep in mind, that as described in the abstract, Pex sits on top of Cython, a fork of the Pyrex project.

Pyrex, at it’s simplest, does three things: it compiles your Python code to C, it allows you to mix C code with your Python code, and finally allows you to write classes – “cdef classes” – whose methods and attributes are accessed at C speeds, 1-2 orders of magnitude faster than methods and attributes of Python classes.

Pyrex compiles your Python code to a sequence of C calls to the Python standard library, for example, Python code:

becomes something like the C code:

Pyrex essentially reproduces the actions the Python interpreter would take at runtime, and writes them to a C file. This removes the overhead of the Python interpreter, however that by itself is usually not significant. However, Pyrex does other optimizations (many of them come from the Cython project), like making [] accesses go faster for list and tuples than for generic Python objects. All told, PyBench – the standard Python benchmark – runs 30% faster when compiled with Pyrex, than when run with Python. It is very probable that you can compile your Python code with Pyrex, with no changes, and have it run faster. Note, most Python code is valid Pyrex code, but not all (one example: import * is not supported). You will likely have to make some small changes, see Pyrex Limitations, and also differences between Pyrex and Cython, because Cython removes some of these limitations.

If you write the following:

both x and y are Python objects, thus x+y is an addition of two Python objects, and happens at Python speed, much slower than C speed. Pyrex allows you to declare and use C variables, much like you would in C, except you have to precede the declaration with “cdef”:

Here, x and y are C ints, and the addition is an addition of C ints, passed by Pyrex through to the C compiler and running at C speed (essentially happening in one instruction), easily 2 orders of magnitude faster than the pure Python version given above.

In a situation when you have an expression where Python objects and C variables are mixed, Pyrex will first convert the C variables to Python objects, for example, here:

x is converted to a Python object, and x+y becomes a sum of two Python objects (notice that this expression now runs at Python speed). Pyrex is able to do this automatic conversion for most of the standard C types (see Pyrex documentation), including all of the ones supported by Pex (see 11).

Similarly, for functions, if you write the following:

the call to func() incurs a lot of overhead because it goes through all of the Python function invocation machinery, the C call stack for such an invocation is something like:

Like for variables, Pyrex allows you to prefix functions with “cdef” and write:

This func() is a regular C function call, with no Python linkage overhead. Note: if you don’t specify a return type, or an argument’s type, a Python object is assumed; the above is equivalent to:

We can also specify the usual C types, e.g.:

Here is an amazing thing about these cdef functions, you can take the following:

change it to:

and have that Python IOError exception correctly plumb through the entire call stack, for essentially no overhead (a boolean check for every function invocation). If you’ve been around C, you are sure to understand this author’s enthusiasm for this functionality.

Pyrex also supports cdef’ing structs, enums, externs, etc. All these things will compile with Pex, but if used as class attributes, will make your class immodest (see 9). In general, as far as Pex is concerned, these features are off the reservation.

Suppose you define a Python class:

and do:

Here is what happened behind the scenes for obj.x and obj.func(), every Python class has a hash containing its methods and attributes, indexed by name. To execute obj.x, Python did a hash lookup for the string “x”, and similarly for obj.func(), a hash lookup for the string “func”. Thus, for any method or attribute access of a Python class, you incur the overhead of a hash lookup. Python also has another, faster, method for attribute access, to use which you specify a list of the attributes an a special __slots__ attribute, however it is still far from C speed.

Pyrex allows you to avoid this overhead by using a “cdef” class (refered to in the Pyrex manual as “extension type”), here is the above example re-written to use it:

Though things look similar, the obj.x and obj.func() are now accessed at the same speed as a C struct attribute, 1-2 orders of magnitude faster than the pure Python.

Though these “cdef” classes are in many respects similar to Python classes, they differ in several important ways. Here is a table summarizing some of these differences:

| class | cdef class | |

| y | y | can have def methods |

| n | y | can have cdef methods |

| n | y | can have cdef attributes |

| y | n | can add new attributes on the fly |

| y | y | def methods visible to Python |

| na | n | cdef methods visible to Python |

| y | n | attributes visible to Python |

| y | y | can use cdef variables inside methods |

| na | y | cdef attributes visible to other cdef classes and Pyrex code ⋆ |

| na | y | cdef methods visible to other cdef classes and Pyrex code ⋆ |

⋆ - These are the two primary reasons for having cdef classes.

| ||

Essentially, a cdef class is a more static creature than a plain Python class, its attributes are set once and for all at compile time – you wouldn’t be too far wrong if you thought of it as a C struct.

Pyrex implements inheritance for these cdef classes, allowing you to derive subclasses, and also, amazingly, implements type polymorphism without sacrificing much in performance (it uses the same “vtable” approach that is used by C++). Type polymorphism is something you immediately discover you need once you start a medium to large size project that uses OOP. For example, suppose you want all your objects to have a fast report() method, which is used when you pass them to a generic report maker function. If you are coming from the Python side, this does not seem very hard; you can lookup the object’s report() method dynamically, at runtime. With a compiled language, like Pyrex, all such lookups must be resolved in a more static fashion – this is where a lot of the speed up comes from.

The usual solution, providing you have type polymorphism, is to derive your classes from a common base class that implements a stub method for report(), and then in the derived class, override this method with something useful. Here is how you would do this in Pyrex:

1import time

2

3cdef class baseclass:

4 cdef void report(me): raise NotImplementedError

5

6cdef class derived(baseclass):

7 cdef void report(me): print "report()␣of␣the␣derived␣class"

8

9cdef do_report(baseclass b):

10 print "report␣at␣time",time.time()

11 b.report() # *****************************************

12

13d = derived()

14do_report(d)

The reason d’etre for all this type polymorphism machinery, is that the obj.report() call in the do_report() function runs at C speed, no matter the type of the passed in object (though note that that type has to derive from baseclass).

When cdef class objects are created typed, like so:

you have access to x’s cdef methods, cdef attributes, and def methods. When created untyped:

you lose access to all the cdef internals, and x appears as an almost regular python object, with the exception that you can not add new attributes. Here is a table summarizing the differences:

| created with | created with | |

| cdef item x = item() | x = item() | |

| access cdef attributes | y | n |

| access cdef methods | y | n |

| access def methods | y | y |

| add new attributes | n | n |

In Pex, you may define class attributes in the class preamble like so:

This is similar to Pyrex, though in Pyrex you would put these declarations in a separate, .pxd, header file.

Pex also allows you to declare attributes directly in the constructor:

When you do so, you may also initialize the class attributes on the declaration line:

:-(Note that decorated ndarray attributes may only be declared in the __init__ function, not in the class preamble.

This not a complete list, these are just features the authors of Pex knew about, and didn’t support. There are likely other unsupported features.

You set the pragmas by putting the following in your code:

See 12 for a complete discussion of the %whencompiling directive. Here is the list of all the pragmas:

| pragma | purpose | default | see section |

| pragma_ndarray_type_check | On/off flag for typechecking of decorated ndarrays | True | 8.2.5 |

| pragma_ndarray_bounds_checks | On/off flag for bounds checking of {} accesses to decorated ndarrays | False | 8.2.6 |

| pragma_gen_all_off | On/off flag to control the generation of all convenience methods for modest and unspoiled classes | True | 9.2.1 |

| pragma_gen_strmeth | On/off flag to control the generation of the __str__() method | True | 9.2.2 |

| pragma_gen_equalmeth | On/off flag to control the generation of the _equal_() method | True | 9.2.3 |

| pragma_gen_richcmpmeth | On/off flag for the generation of the __richcmp__() method | True | 9.2.4 |

| pragma_gen_dictcoercion | On/off flag for the generation of the _todict_() and _fromdict_() dictionary coercion methods | True | 9.2.5 |

| pragma_gen_pickle | On/off flag for the generation of the __reduce__() and __setstate__() pickling methods | True | 9.2.6 |

| pragma_gen_fastio | On/off flag for the generation of the _fastdump_() and _fastload_() fastio methods | True | 9.2.7 |

| pragma_gen_hashmeth | On/off flag for the generation of the _hash_() method | True | 9.2.8 |

Pex brings certain C functions into your regular environment, for example you can do the following:

Here is the .pxi file that brings them all in:

1cdef extern from "stdio.h":

2 ctypedef struct FILE:

3 pass

4

5 FILE *c_stdout "stdout"

6 FILE *c_stderr "stderr"

7

8 int c_fflush "fflush" (FILE *stream) except exits

9 int c_fprintf "fprintf" (FILE *file, char *format, ...) except exits

10 int c_printf "printf" (char *format, ...) except exits

11

12 int c_fwrite "fwrite" (void *, int, int, FILE *) except exits

13 int c_fread "fread" (void *, int, int, FILE *) except exits

14 int c_fclose "fclose" (FILE *) # no ”except exits”

15 # screws up PyFile_FromFile

16 FILE * c_fdopen "fdopen" (int fd, char *mode) except exits

17

18cdef extern from "math.h":

19 double M_E

20 double M_PI

21

22 double c_abs "fabs" (double) except exits

23

24 double c_loge "log" (double) except exits

25 double c_log10 "log10" (double) except exits

26 double c_log2 "log2" (double) except exits

27

28 double c_sqrt "sqrt" (double) except exits

29

30 double c_pow "pow" (double,double) except exits

31

32 double c_exp "exp" (double) except exits

33

34 double c_floor "floor" (double) except exits

35

36 double c_ceil "ceil" (double) except exits

37

38cdef extern from "pex_builtin.h":

39 double c_max(double,double) except exits

40 double c_min(double,double) except exits

41

42 int c_sign(double) except exits

43

44ctypedef void* c_function_pointer

45

46cdef extern from "Python.h":

47

48 ctypedef struct PyTypeObject:

49 # more fields in here, but we don’t care about them

50

51 void* (*tp_new)(PyTypeObject*,void*,void*)

52

53 ctypedef struct PyObject:

54 int ob_refcnt

55 PyTypeObject *ob_type

56

57 int PyString_AsStringAndSize( object obj, char **buffer, int *length)

58 PyObject* PyString_FromStringAndSize( char *v, int len)

59

60 long PyInt_AsLong(object io)

61 int PyInt_Check(object o)

62 PyObject* PyInt_FromLong(long ival)

63 void Py_INCREF(object o)

64 void Py_DECREF(object o)

65

66 object PyFile_FromFile( FILE *fp, char *name, char *mode,

67 int (*close)(FILE*))

68

69 int PyList_Append( object list, object item)

70

71 PyObject* Py_None

72

73 PyObject* PyErr_SetFromErrno( PyObject *type)

74 PyObject* PyExc_IOError

75

76 char* PyModule_GetName( PyObject *module)

77

78 long PyObject_Hash(object ob)

79

80ctypedef char bool

81

82cdef enum:

83 cFalse,cTrue

84

85ctypedef unsigned char uchar

86

87ctypedef unsigned short ushort

88

89ctypedef unsigned int uint

90

91ctypedef long long int64

92ctypedef unsigned long long uint64